Membranous Nephropathy

Contents

What is Membranous Nephropathy?

Membranous Nephropathy (MN) is a kidney disease that affects the filters (glomeruli) of the kidney and can cause protein in the urine, as well as decreased kidney function and swelling. It can sometimes be called membranous glomerulopathy as well (these terms can be used interchangeably and mean the same thing).

Membranous nephropathy is one of the most common causes of the nephrotic syndrome in adults. Nephrotic syndrome includes significant amounts of protein in the urine (at least 3.5 grams per day), low blood protein (albumin) levels, and swelling (edema).

Membranous nephropathy can occur by itself (primary) or due to another disease or underlying cause (secondary). This will be discussed more later, but some things that can cause secondary MN include lupus, cancer, or certain medications. This webpage will focus mostly on primary MN.

Membranous nephropathy is considered an autoimmune disease, which means that it caused by the body’s own immune system. MN is caused by the build-up of immune complexes within the filters (glomeruli) of the kidney itself.The immune system normally creates antibodies to recognize and attach to something (called an antigen). When an antibody attaches to an antigen, this is called an immune complex. Antigens are normally foreign to the body, like a virus or bacteria. However, sometimes, the body can make antibodies that recognize and attach to something in the body itself (not foreign) – these types of antibodies are called autoantibodies. Immune complexes are normally cleared from the blood before causing any problems, but under certain conditions they can accumulate in different parts of the body. In MN these immune complexes (antibodies made by the immune system attached to antigens) get caught in the kidney filters (glomeruli). In most cases of MN, antibodies are made to an antigen that is part of the kidney filter (glomerulus) itself. Together these antibodies and antigens create immune complexes that get stuck in the kidney filter (glomerulus) and cause disease.

Recently the antibody that causes most cases of membranous nephropathy was discovered and identified. In about 70-80% of patients with primary MN (meaning their MN is not associated with or due to other diseases or causes), an antibody called anti-PLA2R is found in the kidney and/or bloodstream. The anti-PLA2R antibody (short for anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibody) attaches to the phospholipase A2 receptor (the antigen). The phospholipase A2 receptor is a protein found in the kidney filter (glomerulus), specifically within a cell called the podocyte which makes up part of this filter (see below). Another antibody called anti-THSD7A (short for anti-thrombospondin type 1 domain-containing 7A) was also discovered but is found in a much smaller number of patients with primary MN, only about 2-3%. This is an antibody to a different antigen, THSD7A, that is also found in the kidney filter (another protein in the podocyte).

What does it look like?

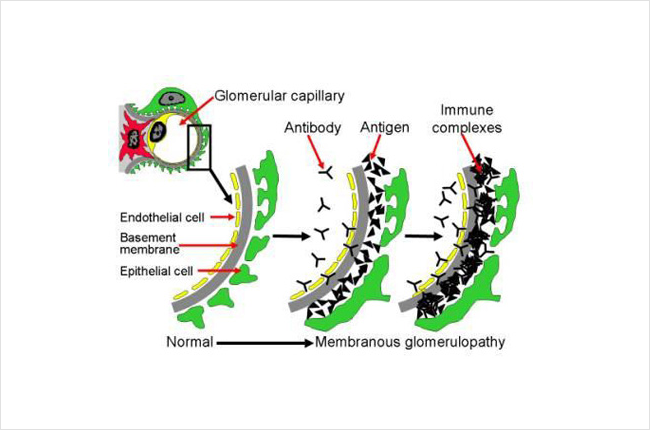

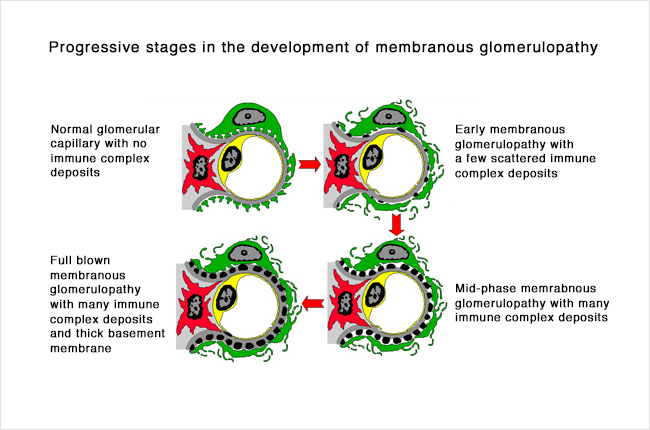

Below is a diagram of how the immune complexes deposit in the kidney. This picture shows a cross section of part of the kidney filter (glomerulus). This includes different layers, including the cells making up the capillary blood vessel (endothelial cell, in yellow), the basement membrane (gray), and layer of kidney cells (podocyte, in green). Blood inside the capillary blood vessel is filtered across these layers and becomes urine. Antibodies (Y-shaped, black in the picture) in the blood stream attach to antigens (triangles, black in the picture) and form immune complexes that get stuck and build up between the layers of the filter (glomerulus). These immune complexes also activate the immune system causing inflammation. Buildup of these immune complexes as well as the inflammation cause the filter to stop working properly and can lead to kidney damage. Normally the filter (glomerulus) allows water, electrolytes and some waste materials through to become urine, and larger things like blood cells and proteins are too big to pass through the filter – so they stay in the blood. However, in this disease, protein and blood cells can leak into the urine because the filter is not working properly.

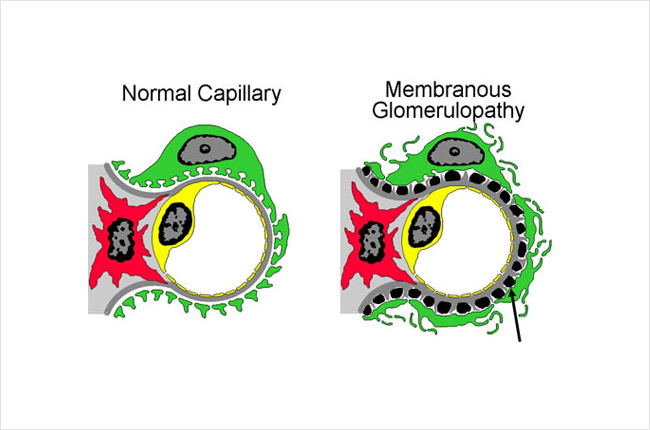

The picture below shows part of a glomerulus, comparing a normal to one affected by MN. On the right, the black spots or lumps (there is an arrow pointing to one) are collections of immune complexes (antigen-antibody complexes). As more of these immune complexes build up between the layers of the filters, it becomes thickened. The kidney cells (green in this picture, called podocytes) that make up part of the filter become damaged from the immune complexes and the inflammation caused by the immune system, and stop working properly. You can see in the picture on the right that the grey layer (basement membrane) has become thicker and has started filling in the spaces between the black spots/lumps. You can also see that the green cell does not look the same as in the normal healthy filtering loop (capillary loop) on the left.

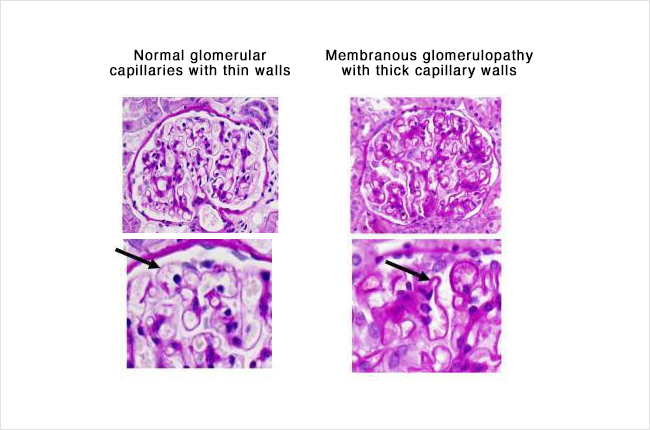

Under a microscope, the filters (glomeruli) in the kidney become thickened, which is where the name membranous nephropathy comes from.

An example of this is shown below – from 2 different kidney biopsy samples. These are cross sections, so the loops are cross sections of the capillary blood vessels and filters. On the left is a normal glomerulus (filter), and on the right the loops in the glomerulus have become thickened in someone with membranous nephropathy. The black arrows in the pictures are pointing out the thickness of the capillary (small blood vessel wall). Notice how much thicker this wall is in a patient with MN (on the right).

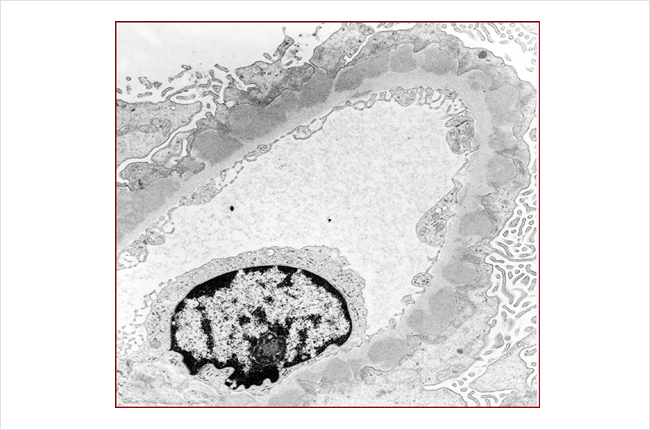

The picture below is another microscope picture of a kidney biopsy sample from someone who has MN. This picture was taken from an electron microscope, which magnifies the sample even more than the pictures above (about a million times bigger than the actual size). The darker grey lumps/blobs are the collections of immune complexes stuck in between the layers of the filtering loop (capillary loop) in the glomerulus. The capillary (tiny blood vessel) is the oval shape extending across the picture, as this picture is showing a cross section of the blood vessel.

Who gets Membranous Nephropathy?

MN is most common in older-middle aged adults, in their 50s and 60s, though can occur earlier or later. It is rare in children. Men are affected more often than women, and it is much more common in Caucasians (versus blacks).

How did I get it?

Though we understand some of how the disease works and how protein in the urine and kidney damage happen, we don’t really understand why it happens to certain people. That is, we don’t know why some people develop these antibodies when most people do not, and why the disease happens when it does (usually later in life) rather than at any other time.

As with other kinds of autoimmune diseases (such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or Crohn’s disease), we think that there are probably multiple things that contribute to the disease developing – meaning multiple things that must occur for the immune system to target and attack/damage the body (rather than just targeting foreign things like infections). Some people may have a gene or genes that make them more likely to have an autoimmune disease (more susceptible to developing them). Though some people may be more likely to get autoimmune diseases if they have family members with autoimmune diseases, MN is not a genetic disease and it is not passed down from a parent to their child. In people who may be at higher risk of an autoimmune disease, certain events or triggers may cause the disease to ultimately develop – such as an infection or other inflammation in the body that might activate the immune system. However, these are hypotheses, and we do not understand at this point why one person gets MN when others do not.

As mentioned before, MN can be primary (an autoimmune disease that is commonly caused by the anti-PLA2R antibody without other associated causes or diseases) or can be secondary (due to another disease or cause). In secondary MN, the same type of kidney injury occurs but is associated with, or caused by, something else. Some of the more common diseases are:

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosis (SLE, or lupus)

- Hepatitis B and C

- Cancers (especially of the lung or colon)

Secondary MN has also been associated with some drugs. The most common are NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, naproxen, or diclofenac). Because hepatitis and cancer can be associated with membranous nephropathy, anyone who is found to have MN should be tested for hepatitis and make sure they are up to date on age-appropriate cancer screening. A blood test can be done to check for hepatitis. Age appropriate cancer screening can include tests such as a pap smear, mammogram, colonoscopy, or CT scan of the lungs (in people who smoke or have smoked). Your doctor can clarify which of these tests are appropriate or necessary for you.

The Nephrotic Syndrome

Membranous nephropathy often causes nephrotic syndrome. Nephrotic syndrome is a group of symptoms or changes that often occur together in someone that is losing a lot of protein into the urine. Nephrotic syndrome can also happen in other diseases that cause a lot of protein to be lost into the urine. Although a lot of people with MN have nephrotic syndrome, not everybody does. Nephrotic syndrome includes these findings:

- At least 3.5 grams of protein in the urine per day (proteinuria). This can be measured on a 24 hour urine collection but can also be estimated on a single urine sample. To estimate the amount of proteinuria from a single urine sample, the urine protein to creatinine ratiois used – this gives an estimate of how many grams of protein would be in a 24 hour urine sample.

- Low blood protein (albumin) levels

- Swelling (sometimes called edema)

It can also include:

- High cholesterol

- Increased risk for blood clots

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptom of MN is swelling (sometimes called edema). This can range from mild to severe. Most people with this disease have some swelling and it is often the first symptom people notice. In MN (as opposed to some other diseases that cause protein in the urine and nephrotic syndrome), swelling usually comes on slowly (over weeks to months) but it can sometimes come on more quickly. It typically starts in the feet, ankles, or legs, but can occur anywhere in the body, including the abdomen, hands or arms, and face.

The swelling in MN occurs because of fluid building up in the body, and specifically in different tissues. When fluid builds up, it can sometimes go into the lungs and cause difficulty breathing or shortness of breath. This is less common than swelling but in people who have this it may be most noticeable when walking or exerting yourself or when lying down flat.

Some people with MN- in particular, people who have nephrotic syndrome (with large amounts of protein in the urine and low blood protein levels)- feel very tired or run-down. We do not know exactly how or why this happens but some people with MN (and other diseases that cause nephrotic syndrome) notice this.

When protein gets through the filter in the kidney and into the urine, the urine can become foamy or bubbly. Some people may notice this change in their urine before they have other symptoms.

There are other symptoms that can occur with MN, but the ones above are some of the most common and the ones that people with MN often notice first.

How is it diagnosed?

Membranous nephropathy is an uncommon disease and diagnosis can sometime be delayed. Since swelling, the most common symptom, can be caused by a lot of different diseases or problems (including kidney, heart, or liver problems), the kidneys may not be identified right away as the cause. Most often it is diagnosed when evaluating someone for protein in the urine (normally there should not be protein in the urine). Some people go to their doctor because of symptoms (such as swelling) and urine tests reveal protein in the urine. Other times, a urine test may be done for another reason (on a routine physical for example) and protein in the urine is discovered. Protein levels can be measured (or quantified) on a 24 hour urine collection or estimated from a single urine sample. Other evaluation usually includes measuring kidney function (from a blood test called creatinine) and doing other bloodwork.

Different kidney diseases – not just MN – can cause protein in the urine, and a kidney biopsy is ultimately needed to diagnose the specific disease causing the protein in the urine. A kidney biopsy is a procedure that involves using a needle to get a sample of kidney tissue to look at under the microscope. This allows the individual glomeruli (kidney filters) to be seen under high magnification. Additional tests can be done on the kidney tissue from the biopsy to help make a diagnosis. Blood tests and measuring protein in the urine can be helpful to understand the severity of the disease and to rule out or look for certain causes, so these tests are often done as part of the workup, but a biopsy is needed to diagnose MN.

Since most people with MN have anti-PLA2R antibodies, bloodwork can be done to check for this antibody. If it is positive, it is very likely that someone has MN. However, a negative test does not mean that someone does not have MN, and a kidney biopsy is important to confirm the diagnosis as well as to provide more information to guide management.

What is the treatment?

Treatment of MN usually involves several different parts that are managed by a nephrologist (kidney specialist).

- ACE-inhibitor or ARB – these are blood pressure medications that can decrease the amount of protein in the urine. These medications are generally the first step in treating MN. Though they were designed as blood pressure medicines, in MN they are used to lower the amount of protein leaking into the urine, and may have the added benefit of helping to control blood pressure if it is elevated. Sometimes these medications cannot be used if someone’s blood pressure is too low (since they can lower blood pressure) or if someone has high potassium levels in the blood (since they can raise potassium levels). However in most people, if there is no contraindication, one of these medications should be used.

ACE-inhibitors (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors) include lisinopril (Zestril, Prinivil), enalapril (Vasotec), ramipril (Altace), benazepril (Lotensin), and quinapril (Accupril). ARBs (angiotensin II receptor blockers) include losartan (Cozaar), valsartan (Diovan), irbesartan (Avapro), telmisartan (Micardis), olmesartan (Benicar), and candesartan (Atacand).

- Fluid medication (diuretic) – these can be used to treat swelling if it occurs. Swelling can be a very bothersome or problematic symptom of MN and so these medications can be an important part of managing the disease. However, they do not treat the MN itself. Diuretics include furosemide (Lasix), torsemide, bumetanide (Bumex), and sometimes others.

- Immunosuppressive medication– not all people with MN will need medication to suppress the immune system, but it is an important part of the treatment for many people who have this disease. Reasons that someone might need immunosuppresive medication include: worsening kidney function, high levels of protein in the urine (especially if they do not get better after a period of observation), or complications from the nephrotic syndrome (such as a blood clot).

Because MN is an autoimmune disease, in which the body’s immune system targets and injury the body’s own tissue (in this case, part of the glomerulus), medications to suppress or decrease the immune system are needed to treat the disease in many people. There are different immune suppressing medications that can be used to treat MN. Since these medications all suppress the immune system, all of them increase the risk for infection. However, they have different individual side effects besides this, and the different possible side effects can be a factor in deciding which one to use.

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)– this is a medication that can be given as a monthly infusion or as a daily pill (by mouth). One of the most common regimens for treating MN includes alternating months of cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids for a total of 6 months (Ponticelli protocol).

- Rituximab (Rituxan)– this is a medication that is given as an infusion, either 4 weekly doses or 2 doses spaced 2 weeks apart. Its effects last about 6 months in the body, and sometimes a maintenance (repeat) dose can be given after 6 months.

- Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine or tacrolimus)– these medications are taken as a pill by mouth, usually twice a day.

- Corticosteroids (prednisone)– this is a medication that is often used with one of other immunosuppressive medications above (most commonly with cyclophosphamide or with one of the calcineurin inhibitors). Corticosteroids are not effective by themselves for treating MN but can be used as part of other regimens.

- Cholesterol medication – because cholesterol levels can be elevated in people with nephrotic syndrome, treatment may include a medication for this. The most common type is called a “statin” and these include atorvastatin (Lipitor), lovastatin, pravastatin (Pravachol), and rosuvastatin (Crestor).

- Blood pressure management – blood pressure is often elevated in people with kidney disease, including MN. It is important to keep blood pressure well-controlled to prevent damage to the kidneys. In addition to an ACE-inhibitor or ARB that can help with protein in the urine (above), there are many other medications that can be used to treat high blood pressure. Limiting salt intake can help with blood pressure control as well as with decreasing swelling.

- Blood thinners – because people with nephrotic syndrome (protein in the urine, low blood protein levels, and swelling) are at higher risk for blood clots, treatment may also include a blood thinner to prevent blood clots. The decision of whether to start a blood thinner is based on balancing the risk of having a clot with the risk of having bleeding from being on a blood thinner. There is a website that you can use with your doctor to help decide if a blood thinner would be beneficial for you. In most cases, the blood thinner should be stopped when the nephrotic syndrome gets better and blood protein levels go up.

Finally, if the MN is considered secondary to something else, then it is most important to treat the underlying disease (infection, cancer, etc.) or to stop the causative drug. This is often enough and treatment with immune suppressing medications can be avoided.

What are my chances of getting better?

Up to a third of patients diagnosed with MN will go into remission spontaneously within 5 years, even without immunosuppressive therapy. With treatment, most patients’ disease will go into remission. Complete remission means stable (or improved) kidney function and protein levels in the urine decreased to normal. Partial remission means stable or improved kidney function plus protein levels in the urine decreased to less than half of original levels and not in the nephrotic syndrome range (<3.5 grams/day).

However, relapse is common in MN, and patients that go into remission either spontaneously or in response to immunosuppressive can have the disease return later. Long term (over decades) about 1/3 of patients will progress to end-stage kidney disease (kidney failure needing dialysis), about 1/3 will have continued protein in the urine without kidney failure, and about 1/3 will be in remission.

Things that predict a better long-term outcome in MN include lower levels of protein in the urine, being female, being younger (less than 60), and achieving remission.

Kidney Transplant in Membranous Nephropathy

Unfortunately, some patients diagnosed with MN will eventually progress to kidney failure. Fortunately, kidney transplant is a treatment option for some people.

Read general information about kidney transplant here.

Will the membranous nephropathy come back in my kidney transplant?

There is a 40% chance that MN will return in a transplanted kidney. Unfortunately, there are no factors that have been identified to give us an idea of patients at risk for this problem. Generally, recurrence of the disease will occur in the first 2 years after transplant.

Is there any treatment for membranous nephropathy that comes back in a transplant?

There have not been any trials to evaluate different therapies for MN that comes back in a transplanted kidney. However, Rituximab is one option that has been used successfully for treatment.

This page was reviewed and updated in September 2018 by Shannon Murphy, MD.