IgA Nephropathy

Contents

What is IgA Nephropathy?

IgA Nephropathy is a relatively common kidney disease. It affects millions of people worldwide. It is a disease that affects the filters, or glomeruli, of the kidneys. IgA is characterized by the hematuria it causes, which just means blood in the urine. This blood may be visible to the naked eye or only seen under a microscope. Over time this disease can damage the kidney’s ability to clean the blood properly. Most people with this disease lose kidney function very slowly, or not at all.

IgA Nephropathy is named for the deposits of IgA that can be seen stuck in the kidney filters when viewed under a microscope. IgA is an immunoglobulin– a normal component of a healthy immune system. These components normally attach themselves to infection in the body and trigger the immune response. This works to eliminate the infection. In this disease, a defective form of IgA gets bound to another IgA molecule instead of an infection. This forms an immune complex. This immune complex can become stuck in the kidney. Here it activates the immune system just like it would if it were fighting off infection. The immune system activation causes swelling and damage to the kidney itself. This disease may be suspected from certain symptoms (see below). However, a diagnosis of IgA Nephropathy requires a kidney biopsy. The sample of kidney can then be viewed under a microscope and the diagnosis confirmed.

What does it look like?

First, a quick look at the kidney. Most people have two kidneys, one on each side of their lower back. All of the blood in your body passes through your kidneys many times during the day. Each time blood goes through some of it gets filtered and cleaned by the glomeruli. This cleaning is how your body gets impurities out of the blood (and removes extra water). Some of the cleaned blood becomes your urine. Urine isn’t red like blood because the red blood cells, which give blood its color, are too big to fit through the filters. A glomerulus (one glomeruli) is just a tiny bag of blood containers through which blood gets filtered. All of the clean blood (urine) runs into tubes (ureters) which eventually lead to your bladder.

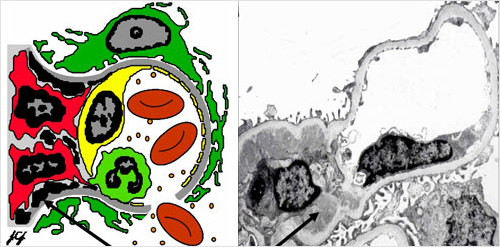

The drawing below shows how this disease affects the kidney. Pictured is a single blood vessel from a kidney filter, shown in cross section. The red disks are red blood cells. They normally should remain inside the vessel itself (shown as a ring of yellow, gray, and green).

The IgA deposits have activated the immune system and damaged the vessel wall. Therefore, red blood cells (and protein, the tiny yellow dots) are spilling out the bottom of the vessel and into the urine.

Mesangial immune deposits

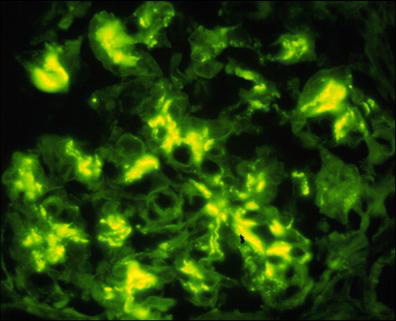

Below is a picture, from the actual kidney biopsy of someone with IgA Nephropathy. Shown is a single filter in which the actual IgA deposits have been stained florescent green.

How did I get it?

IgA is an autoimmune disease. This is a disease in which a person’s own immune system damages their own body. Scientists know that the IgA immune complex (see above) causes the inappropriate immune response. But it is not yet known what causes the defective IgA in the first place. It likely has both genetic and environmental components. A person is born with a predisposition for the disease, and then some sort of “trigger,” for example an infection or food exposure, turns the disease “on”.

IgA commonly occurs in Caucasians and Asians. It is relatively uncommon in those of African descent. It is twice as common in males as females. Though it potentially affects any age group, IgA is most commonly diagnosed in early and middle adulthood.

What are the symptoms?

Blood in the urine, either constant or occasional, is the most common finding in people with IgA. Sometimes this blood can become visible as well. Though when it does, the urine typically appears browner or “cola” colored, rather than bright red. Bouts of visible blood in the urine from this disease often occur during or immediately after other short-term illnesses, such as an upper respiratory infection.

In addition to blood in the urine, people with IgA can have protein in the urine as well. The amount of protein in the urine is generally less than 3.5g. It can sometimes result in significant leg swelling and fluid retention.

IgA can be suspected from blood or protein in the urine and other symptoms. But it can only be diagnosed by a kidney biopsy.

What is the treatment?

This disease is common, but there is no single treatment about which all doctors agree. This is in part because of the disease tends to progress very slowly, if at all. Many of the drugs that could be used in treatment can be very harmful.

It is generally accepted that blood pressure control and limiting the amount of protein in the urine are of primary importance. Both of these goals can often be accomplished with the use of two types of blood pressure medications. ACE-inhibitors (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors) and ARBs (angiotensin II receptor blockers) both help to reduce blood pressure. Another commonly used agent is Fish Oil. Studies do not agree on its true benefit. However, its lack of serious side-effects leads many doctors to recommend it.

This disease is essentially an over-activation of the immune system. Therefore, many immunosuppressive drugs have been tried with varying success. The most widely used are steroids, given either through a needle, by mouth, or both for at least 6 months.

IgA often progresses slowly. Doctors may simply follow some patients with normal renal function and minimal protein in the urine without starting any therapy at all. It is the disease’s generally slow progression that has made it difficult for doctors to decide on the one “best” treatment.

What are my chances of getting better?

Some patients spontaneously undergo a complete remission of symptoms and never experience a loss of kidney function. More often, the symptoms will stabilize, or the disease will progress slowly. On average, at 20 years (from diagnosis), 20% of patients will have moved to end stage kidney disease. This requires either dialysis or a kidney transplant.

Rarely, a more rapidly progressive type of IgA is seen on biopsy. In these patients, immediate and aggressive immunosuppression is generally needed.

Kidney Transplant in IgA Nephropathy

A portion of the patients diagnosed with IgA nephropathy will eventually progress to renal failure. Fortunately, kidney transplant is a treatment option for these patients.

Read general information about kidney transplant here.

Will the IgA nephropathy come back in my kidney transplant?

A return of this disease is fairly common after a kidney transplant. If you did a kidney biopsy of all transplant patients with IgA nephropathy, about 60% of them would have evidence of the disease in the biopsy sample. But not all would have symptoms or other abnormal test results. About 20-40% of patients actually have abnormal protein or blood detected in their urine due to a return of the disease.

Recurrence usually happens, on average, around 2.5 years after the transplant. But it can occur at any time.

Is there any treatment for IgA nephropathy that comes back in a transplant?

There are no specific treatments for this disease in transplant patients. The treatment is similar to the treatment of the disease in your original kidneys. This includes blood pressure control and immunosuppressive medications for more severe cases.

If the IgA nephropathy does come back, will it cause me to lose my kidney transplant?

Fortunately, renal function is usually good for several years after recurrence of IgA in a transplant. After about 5 years, the rate of kidney loss due to the disease is increased. About 40% of patients who have recurrent IgA will eventually lose their kidney because of the disease. However, it can take up to 10 years or more for that to happen.

IgA Nephropathy Podcast

This UNC Kidney Center podcast features Dr. Ron Falk discussing IgA Nephropathy, and covers questions patients might frequently ask when first diagnosed with IgA, such as “What is IgA Nephropathy?” and “How did I get it?” and covers other questions of interest such as “Are fish oils helpful?” and “Should patients have their tonsils removed?”